Book Review: Moral Uncertainty

What to do when you don’t know what to do?

The book and this post try to discuss morality in a curious—if at times challenging—way that often goes at the heart of values many of us hold dear, if you’re not into that, no worries, but best to avoid reading either in that case.

I recently joined a Facebook group for effective altruism in the Seattle area. I went to a social meeting for the group and it was an enjoyable bunch so I was looking forward to participating in their book club which seemed to focus on non-fiction reads. This was even better for me since I have some trouble finding partners in crime to apply enough social pressure to get me to actually finish some of the books on my list I want to read but have trouble reading alone. This month the group proposed Moral Uncertainty by William MacAskill, Krister Bykvist, and Toby Ord. The book is actually available free online if you can make it through 200+ pages of reading a PDF, I only barely made it (thank goodness for the social pressure).

One of the things that puts a lot of folks off of utilitarianism is that it asks quite a lot of folks and sometimes seems to imagine its adherents can have the time to actually work out all the implications of their actions (something that seems at best implausible). One of the attractions, for me, of utilitarianism as a moral philosophy however is that I believe it forces us to be quite humble in our moral proclamations and cautious in our actions. It’s very difficult to know, for sure, if your preferred political proclivities will lead to the most good in the future so I think it asks us to be more understanding and curious in the face of our epistemic rivals. To the extent that I try to pursue a vegetarian diet it was almost completely by this sort of logic; I’m not certain that animals have moral weight—or at least moral weight that can scale up to something I should worry about—but it seemed very plausible to me that they might. Moreover, when thinking about what sort of faults our decedents will find in our behavior many centuries from now, the conditions of factory farming seem like a front runner for the sort of thing thing we’d be harshly judged for.

This book was quite attractive as it offered a book length treatment on just that sort of logic from folks who have thought a lot about practical ethics; Ord and MacAskill have a good claim to be the founders of the effective altruism (EA) movement. I’ve read books by each of them and thought they were compelling and so I was excited to see what they had to say here.

The most obvious difference between the books I’d read by them in the past and this one was the density, I wouldn’t necessarily recommend this book to most folks, it’s quite thick with technical philosophical jargon that, even for this pretty avid philosophical hobbyist, was pretty far beyond me at times. However for the most part, when skimming the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy didn’t get me what I needed, I happily noted it down with the hopes someone from the book club would know what on earth they were saying and moved on.

What if morality’s a math problem

I think the central conceit of effective altruism is that morality can ultimately be broken down to a math problem. This is met with abject horror in some circles and often simply dismissal but I’m pretty on board so I was excited to see what they had to say here.

The naïve approach to moral uncertainty is simply to posit that you might have different credences you grant to different moral intuitions you have. An example they use is as follows:

Jane is at dinner, and she can either choose the foie gras, or the vegetarian risotto. Jane would find either meal equally enjoyable, so she has no prudential reason for preferring one over the other. Let’s suppose that Jane finds most plausible the view that animal welfare is not of moral value so there is no moral reason for choosing one meal over another. But she also finds plausible the view that animal welfare is of moral value, according to which the risotto is the more choiceworthy option.

Here Jane isn’t really sure if animal lives matter but, since she does ascribe some plausibility to animal welfare being important, and would find either meal equally enjoyable, she may as well choose the veggie option. This result is pretty obvious since it has a “may as well” quality to it where Jane doesn’t really face any tradeoffs in her decision. The authors of course go on to complicate matters.

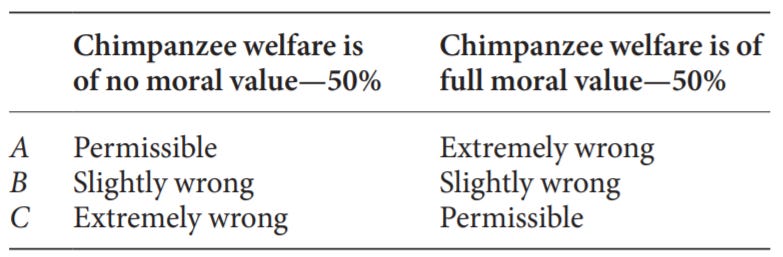

Susan is a doctor, who faces two sick individuals, Anne and Charlotte. Anne is a human patient, whereas Charlotte is a chimpanzee. They both suffer from the same condition and are about to die. Susan has a vial of a drug that can help. If she administers all of the drug to Anne, Anne will survive but with disability, at half the level of welfare she’d have if healthy. If Susan administers all of the drug to Charlotte, Charlotte would be completely cured. If Susan splits the drug between the two, then they will both survive, but with slightly less than half the level of welfare they’d have if they were perfectly healthy. Susan is certain that the way to aggregate welfare is simply to sum it up, but is unsure about the value of the welfare of non-human animals. She thinks it is equally likely that chimpanzees’ welfare has no moral value and that chimpanzees’ welfare has the same moral value as human welfare. As she must act now, there is no way that she can improve her epistemic state with respect to the relative value of humans and chimpanzees. Her three options are as follows:

A: Give all of the drug to Anne

B: Split the drug

C: Give all of the drug to Charlotte…

Here Susan has to make a pretty tricky trade off, she grants equal credence to each moral position however the implications of choosing the best option for each of the cases results in a moral tragedy if she’s wrong, and she’s only 50% sure she’ll be in the right. The authors propose—in what will be the first of many potentially controversial opinions if you don’t think math and morality have much in common—to choose B in this case because you’ll only be acting “Slightly wrong” at worst (or best) and any other choice gives you a 50% chance of committing a morally unspeakable act.

I’m moved by this logic and think, to the extent one would ever find themselves in the unfortunate position of being trapped inside a thought experiment, that B is probably the best you can do. This in turn gets the ball rolling on the somewhat unique way the authors intend to use the word ought in this book. To say that Susan ought to choose B, they’re not saying that either of her moral positions are mistaken, only that, when faced with the realities of epistemic and moral uncertainty, the best option might not be what any moral intuition says is best!

How deep the rabbit hole goes

One of the chapters I enjoyed the most was a meditation on the implications of moral uncertainty in practical ethics. The authors contend, and I largely agree, that at first blush, it will seem that moral uncertainty demands certain behavior because the magnitude of moral transgression is so high in some cases that even if you’re pretty sure it doesn’t matter, you should take seriously what the implications would be if you’re wrong.

They offer an illustrative example of how empirical uncertainty maps here with a thought experiment called Speeding.

Julia is considering whether to speed round a blind corner. She thinks it’s pretty unlikely that there’s anyone crossing the road immediately around the corner, but she’s not sure. If she speeds and hits someone, she will certainly severely injure them. If she goes slowly, she certainly will not injure anyone, but will get to work slightly later than she would have done had she sped.

This pumps a strong intuition that it’s simply not worth it to speed because the moral risk is so great. The authors then go on to try and extend this analogy to two areas which are frequently discussed in moral philosophy especially when discussing the topic of moral uncertainty; vegetarianism and abortion.

Under this initial pass, if one gives any credence at all to the the idea that animal lives or unborn lives have moral significance, one is strongly compelled towards action that would protect those lives. There’s an intuition that, since there’s no serious folks proposing the case that killing and consuming animals is morally positive (likewise no one is saying abortions for the sake of abortions is a moral good) the uncertainty in the machine directs us towards vegetarianism and a pro-life stance. However as the authors are wont to do, wrinkles are added.

Consider vegetarianism. Moller states that, ‘avoiding meat doesn’t seem to be forbidden by any view. Vegetarianism thus seems to present a genuine asymmetry in moral risk: all of the risks fall on the one side.’ Similarly, Weatherson comments that, ‘the actions that Singer recommends. . . are certainly morally permissible . . .One rarely feels a twang of moral doubt when eating tofu curry.’

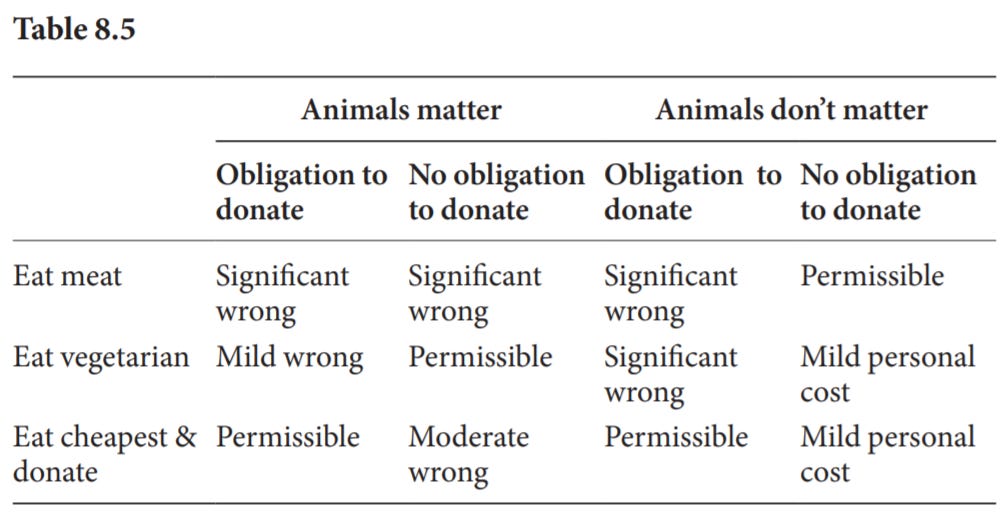

That is, the moral uncertainty argument for vegetarianism got its grip because there was supposedly no or almost no possible moral reason in favour of eating meat. Once we consider all the implications of moral uncertainty, however, this is no longer true.

We saw that, given moral uncertainty, it’s good (in expectation) to bring into existence beings with lives that are sufficiently good (above the critical level c* ). And some types of animals raised for consumption appear to have moderately happy lives, including cows, sheep, humanely raised chickens, and pigs.17 Depending on exactly how one distributes one’s credences across total views and critical-level views, one might reasonably judge that these lives are above the critical level c* .

Essentially, the initial considerations are hardly all there is if we fully take on board the depths of our epistemic precarity. If—and here we have to imagine a different reality than the one we find ourselves in—all or most animals consumed for food had a relatively happy life until they were humanely killed after having experiences we might say lead to a fulfilling cow life, if we could know what it was like to be a cow, then on balance it may be better to have large populations of animals bred and given these worthwhile lives even if they are killed in the end (we do all die after all).

Further, there’s an argument that vegetarianism, while often fairly cheap in comparison to many western diets, is not always cheapest option when choosing what to eat. The money that one spends on the vegetarian option could instead be saved and directed towards an effective charity that ends up saving a human life (or several), which you may evaluate as valuable enough to offset the moral bad of killing the animal (especially when taking into account one’s uncertainty on the moral ratio).

A similar treatment is given to abortion:

Similar considerations apply to abortion. First, even though on Ordinary Morality, the decision whether to have a child is of neutral value, on some other theories this is not the case. In particular, on some moral views, it is wrong to bring into existence even a relatively happy child. On person-affecting views there is no reason in virtue of the welfare of the child to have a child; and if you believe that the world is currently overpopulated, then you would also believe that there are moral reasons against having an additional child. On critical-level views of population ethics, it’s bad to bring into existence lives that aren’t sufficiently happy; if the critical level is high enough, such that you thought that your future child would probably be below that level, then according to a critical-level consequentialist view you ought not to have the child. On environmentalist or strong animal welfare views it might be immoral to have a child, because of the environmental and animal welfare impact that additional people typically have. Finally, on anti-natalist views, the bads in life outweigh the goods, and it’s almost always wrong to have a child.

This means, again, that we cannot present the decision of whether to have an abortion given moral uncertainty as a decision where one option involves some significant moral risk and the other involves almost no moral risk. We should have at least some credence in all the views listed in the previous paragraph; given this, in order to know what follows from consideration of moral uncertainty we need to undertake the tricky work of determining what credences we should have in those views. (Of course, we would also need to consider those views according to which it’s a good thing to bring into existence a new person with a happy life, which might create an additional reason against having an abortion.)

It goes on to discuss that similar opportunity costs should likely be made, as were made for vegetarianism. For potential western parents, the resources, on average used to raise a child could likely save the lives of several people in countries where the resources will go further and, even if you grant a relatively low credence to a utilitarian calculus, getting it wrong could imply a negative moral act.

Where do we go from here

If you’ve made it this far without closing the window in disgust you may be left with a similar level of moral and existential dread as I faced when finishing up the book (and we should probably try to grab a drink sometime and hash it out). The authors do a lot of complicate our moral reasoning but not a lot to help us sort out what we should do1. This is to say nothing of the fact that, once you’ve scratched the surface of moral uncertainty, there’s a creeping worry that it might just be turtles all the way down. What if even in the event you somehow solve this seemingly intractable math problem, you have reason to believe that you may not be evaluating ground truth?

The authors discuss their view that you should likely spend much more time and resources in determining what the right thing to do is than most of us do but this assumes this will cash out in a place where we’re morally certain (or at least more so than when we began) but I’m not sure I see the compelling argument we should be confident that’s the case. What’s more, if we get some of these modifiers, numerators and denominators wrong along the way, the result which is worked out can be radically different.

If you’ve hoped this post was going to do any more than the authors to resolve what we should do in our uncertain world I’m afraid I have to let you down. Both I and the authors are pretty bullish on the suggestions GiveWell gives however, and since tomorrow’s Giving Tuesday, maybe that’s not a bad place to start.

They do go into quite a bit of detail on the similarities between social choice theory and what we should do in moral uncertainty including the proposal that our moral intuitions should get to vote and interestingly—for those who are voting theory nerds—that they should vote using Borda voting instead of Condorcet voting (the opposite conclusion to the one normally reached by voting theory nerds) mainly due to the fact that whereas often times there’s concerns of strategic voting, when your moral intuitions are voting, this is largely nonsensical and can be ignored.